On the road to entrepreneurship, researchers must adapt to a business-world mindset

While the expectations to set up research-intensive businesses are high and increasingly more opportunities are provided to finance business ideas, the researcher and the entrepreneur have very different outlooks. How can a researcher become an entrepreneur, and what to consider on this journey? In an interview with Kadri-Ann Mägi, the founders of Silklytics OÜ, chemist Hanno Evard and molecular biologist Airiin Laaneväli shared their experiences.

From time to time, we hear news reports of supermarkets calling back products that are, for some reason, harmful to human health. For example, pesticides have been discovered in food products after reaching the market, in quantities that pose a health risk, or the level of another substance has exceeded the limit.

Silklytics, a University of Tartu spin-off, is developing a rapid test for detecting chemical compounds, which can soon help make such situations a thing of the past. It will be an alternative to the currently used, analytical chemistry-based laboratory tests, which are accurate but expensive and time-consuming. The test developed by Silklytics is just as precise but much cheaper and takes just an hour instead of a week or more to get the result.

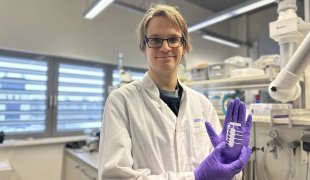

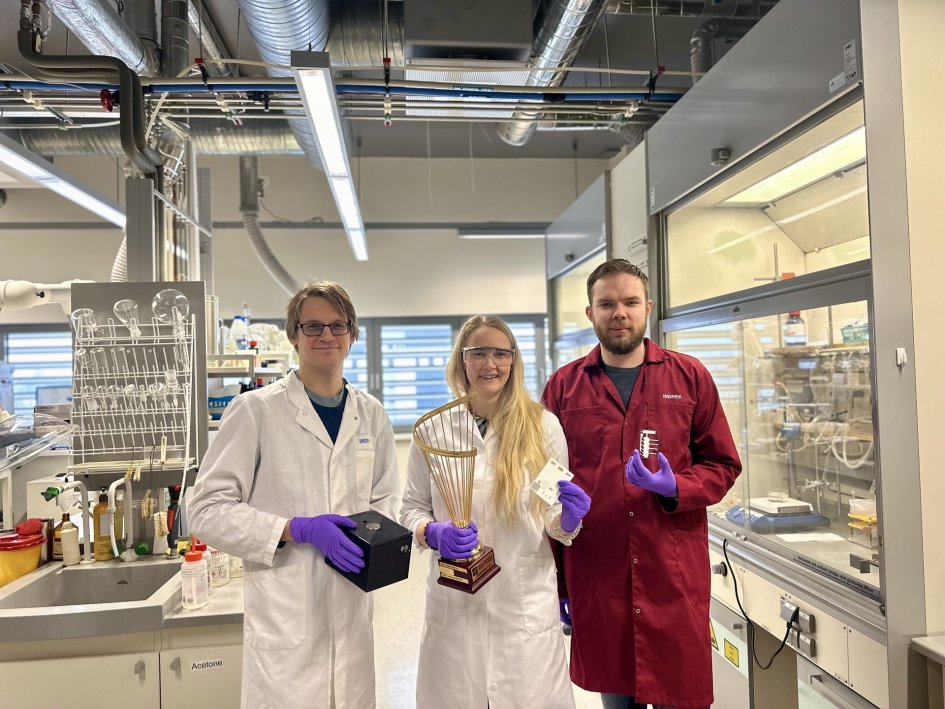

Silklytics was founded by three university researchers: Hanno Evard, Airiin Laaneväli and Indrek Saar. I visited the team in their laboratory and talked to Hanno and Airiin to learn more about the test development process and how they became entrepreneurs.

Making a career in academia is not easy, nor is being an entrepreneur. How did you get the idea to combine these two seemingly very different worlds?

Airiin: I have always wanted to do applied science. Entrepreneurship is one way to do that. I was interested in economics and entrepreneurship, including business, at secondary school already. Besides entrepreneurship, medicine is also important to me. We are currently developing the Silklytics test for the agricultural sector, but our next step is to enter medicine. So, you could say that I am fulfilling my dream – integrating science, entrepreneurship and medicine.

Hanno: I didn’t choose science because I necessarily wanted to do applied science. However, when I had already entered, to some extent, the academic world, it seemed that research is often done to write articles, and articles are written to get research grants. And there is no direct practical result. This made me want to actually do something. After my doctoral and postdoctoral studies at the University of Helsinki, I got a research grant, which I used to start doing applied research.

Airiin: Earlier, we used Hanno’s research funding. Then, we got into an accelerator that accepted ten European companies, including two from Estonia, one was us. We had to establish a legal entity to get in, so we founded a company in 2023 although we had started test development in our research team in 2020 already.

Did Silklytics OÜ start from research with applied potential?

Airiin: It did! We have made great progress. The first year was extremely challenging. We did not have the result we had hoped. The business team to whom we presented our work didn’t understand what we were doing. For half a year, I synthesised a substance in the lab that would have been very important for the test, but in the end, this particular application didn’t produce the results we needed quickly enough, and we had to find an alternative solution.

Hanno: Researchers in entrepreneurship can easily find themselves in a bad situation when it turns out that there is no real market for the technology or product they have developed because it does not solve any problem. Our team wanted to avoid that, so we started development differently. First, we interviewed people from various fields to understand their problems and whether or how they solved them. This mindset has guided us from the very beginning.

Airiin: Yes, we have always been involved in both research and business development.

Silklytics has three founders. Are you similar or different? Do you complement or balance each other?

Hanno: I believe we are rather different and balance each other. Airiin has an outstanding sense of business. I like to come up with a lot of ideas. Indrek is an excellent problem-solver and very good at engineering.

What is your team like?

Hanno: All our team members – there are seven of us – are researchers. I wanted to collaborate with Airiin because I immediately understood she was both a scientist and an entrepreneur. I didn’t know anyone else like that.

Airiin: I love being in Hanno’s team; he is a very good leader. He is calm and values the quality of work and the team members’ well-being; he wants everyone to feel good and makes sure they do. Indrek’s precision and patience in creating and testing design solutions are admirable. Another thing that is important for me is that our team is international: one member is from Mexico, and one is from Azerbaijan.

Does a researcher’s mindset differ from an entrepreneur’s, and how much?

Hanno: They are fundamentally different. For example, as a researcher, I don’t have to go and interview the potential users of the technology we develop. The way how we talk of numbers is also different. A researcher tries to give you a concrete and as precise as possible number, also to investors who ask, for example, about the potential market size. In the business world, however, you need to be a salesperson and think more or less about the big picture rather than focusing on details.

How did you adapt to this change? Has it been easy?

Hanno: It definitely hasn’t been easy. I am not quite sure if I’m good at it even now. I think I've got the basics and understand the mindset of the business world, but I surely need more practice.

Speaking of numbers, how similar is, for example, applying for a grant as a researcher to getting funding from an investor?

Hanno: In a grant application, researchers “sell” their research idea: they have to explain how novel it is, in what detail and how thoroughly it has been thought through, and how likely it can be achieved. Investors are not interested in ideas. They want to know how they will get their money back. They will get it back when we go out into the real world and solve a real problem.

The university has various measures and programmes to support researchers on their entrepreneurial journey. For example, the preincubation programme “From Science to Business”, in which your team also participated a few years ago, is about to start. What other support would a researcher need on this journey?

Hanno: The more the university supports researchers to help them take the first steps in the business world, the better. This change can be uncomfortable at times. We were in the “From Science to Business” programme for three years and made it to the accelerators from there. Now, we can apply for funding from different sources and maybe recruit an expert focusing only on business development.

Until then, you work on business development yourself. Doesn’t that distract you from research?

Hanno: No, on the contrary, the two support each other.

You mentioned that the business world and what goes with it is quite an unfamiliar environment for a researcher. What about the achievements there? Do they offer more pleasure than academic achievements?

Hanno: Yes, I don’t even find them comparable. When an interviewee says there is a great need for the product we are developing because it is necessary for people, and I know we have the team and the skills to make it ... It’s a great feeling!